Brent Sturlaugson

Brent Sturlaugson is a licensed architect and assistant professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at Morgan State University. Brent has received awards from the American Institute of Architects, the Society of American Registered Architects, and the Institute of International Education, and his work has been published in Places Journal, CLOG, Society & Space, PLATFORM, and JAE. Brent received a Bachelor of Architecture from University of Oregon and a Master of Environmental Design from the Yale School of Architecture.

Blend House

Date: 2019

Type: Accessory Dwelling Unit (Unbuilt)

Site: Lexington, KY

Team: Brent Sturlaugson, Zane Slone, Kristy Stambaugh

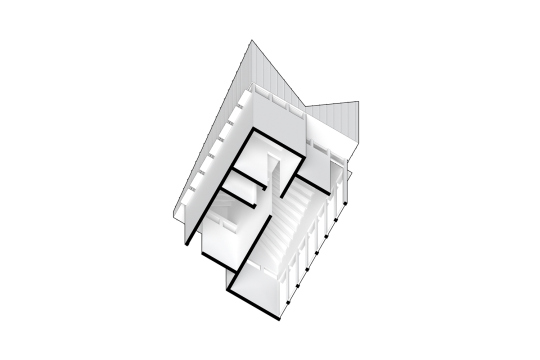

Blend House draws inspiration from the continuously changing character of the built environment. At its entry, the house presents a roof profile that reflects much of the existing residential landscape. At the rear of the house, the roof is inverted to create an unconventional profile that signifies a departure from existing practices. Between these profiles, the underside of the roof creates a ruled surface on the ceiling of the semipublic spaces. Adhering to universal design principles, the prototype also seeks to change neighborhood demographics to be more inclusive of elderly or disabled residents.

Blend House also enlists passive design principles to facilitate natural heating, cooling, and lighting. To lower the impact on existing sewer infrastructure, it detains rainwater onsite for on-site irrigation, and to reduce its carbon footprint, many of the structural and finish materials derive from sustainably managed forests. Concerned with maintaining privacy between the main house, Blend House demonstrates ways of orienting views and creating protected outdoor space, among other considerations. Guided by socially and environmentally sensitive design principles, the project seeks to promote progressive change within the existing urban context.

Soul House

Date: 2019

Type: House (Unbuilt)

Site: Cook County, MN

Team: Brent Sturlaugson

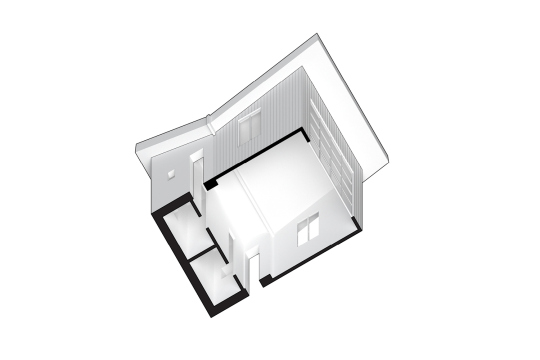

Soul House is a commissioned design for a client seeking refuge in the dense forests of northern Minnesota. The house adheres to universal design principles, and is conceived as a space for aging in place. Because of its remoteness, much of the energy and material for the house is harvested and produced on-site.

The spatial organization of Soul House is characterized by a looping enfilade around a concealed courtyard. Along the primary axis, the space flows through the semipublic areas of the house, leading to the greenhouse. Along the secondary axis are the more private areas of the house, which lead to the back porch. From these circulation axes, rooms within the house are connected by visual axes, giving the house a sense of porosity and depth within a small footprint.

Soul House responds to its specific environment in several ways. The forest clearing to the south of the house permits the winter sun to enter the greenhouse, and the orientation of the roof allows for direct solar gain in the main gathering space. Harvested trees from this clearing are milled on-site to produce the primary structural elements and exterior cladding, thereby reducing the transportation costs and carbon footprint of material acquisition. In order to maintain a more regulated interior environment, the greenhouse acts as a thermal swing space, which greatly varies in temperature from day to night and acts as a buffer zone to the main gathering space. The geometry of the roof of the Soul House is multifunctional. In addition to supporting energy efficiency, the roof is designed to collect rainwater to be used for irrigation and graywater plumbing.

At the core of the house is a concealed courtyard. From inside, the courtyard is barely perceptible, accessed only by discrete entrances. The courtyard itself aids cross ventilation, and it creates a protected outdoor space where only the sky is visible.

Bale House

Date: 2011

Type: House (Built)

Site: Black Hills, SD

Team: Brent Sturlaugson, Soren Sturlaugson, Ben Hurley

Bale House is a small residence for an artist seeking to embrace the surrounding environment while preserving flexibility of the interior spaces. The project goals called for a small footprint of affordable construction that minimized environmental impacts while maximizing flexibility. To meet these demands, internal structural elements were avoided in order to widen the adaptability of the space. The form derives primarily from the natural elements present on the site. As such, the roof planes slope inward, gathering rainwater into cisterns that serve as irrigation for on-site food production. The southern façade—almost entirely glazed with an insulated glass garage door—insolates the exposed concrete slab in winter months and shades it in the summer. Robust straw bale insulation harvested from neighboring grain fields keeps the harsh winter winds at bay and creates a sculptural quality in the interior spaces. Finally, a frost-protected shallow footing conserves nearly half the amount of concrete compared to conventional footings in the area. Together, these design strategies harness existing natural processes for applications in everyday life.

Supply Chain Materialism

Brent Sturlaugson, “Supply Chain Materialism,” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Annual Conference Proceedings 108 (Washington, D.C.: ACSA Press, 2020)

The goal of this paper is to unsettle prevailing assumptions of sustainability in architecture by analyzing the supply chain of building materials. By closely following the transformations of architectural materials and those that transform them, the tangible effects of design become more apparent (e.g. material extraction, environmental pollution, waste streams), and the intangible forces become more visible (e.g. economic incentives, labor abuses, political spending). The paper begins by outlining several theoretical and representational challenges of supply chains, followed by examples of how these ideas can be applied in teaching and practice.

Methods of representing supply chains fall into two categories. The first category documents supply chains in abstract or distanced representations, in what Donna Haraway might call “a view from nowhere.” These often take the form of maps, diagrams, or explanatory text that attempt to communicate the networked topology of material production. However, the comprehensive ambition of these representations often compromises their affective appeal. The second category adopts a momentary or situated representational strategy, often in the form of installations, images, or narrative text. These representations aim to highlight specific spaces or embodied relationships that speak to the character of the process, what Haraway might consider the “partial perspectives” that offer a more visceral understanding of a process. These types of representations, however, often risk underselling the extent to which decisions affect distributed sites and relationships.

To better grasp the impacts of design, this paper argues for hybrid approaches that draw from both methodological categories. It explores these ideas by describing the format and content of a graduate seminar called “Supply Chain Materialism.” The course itself is structured as a speculative supply chain. At the beginning of the semester, students select an everyday construction material (e.g. steel, concrete, glass, plastic, wood, brick, silicone) and document its transformations alongside the weekly theme. Paired with this independent research, the course offers a range of theories that help frame a more critical understanding of sustainability, drawing on texts in architecture and other spatial disciplines. The course also presents a catalog of spatial practices that align with different stages in the supply chain, including include art installations, activist demonstrations, architectural projects, curated exhibitions, and performances.

Throughout the semester, students demonstrate their understanding of the course content through three representational techniques. First, students make collages using images clipped from trade magazines. These collages exploit the disjointed nature of material production by juxtaposing images of the seemingly dissociated sites, actors, and effects. Second, they create a narrative that documents specific activities involved in each stage of production of their selected material. Third, students design a folly that highlights the invisible aspects of their reconstructed supply chain. By creating a useless object out of a useful material, the folly seeks to unsettle assumptions about the ubiquitous materiality of building design through techniques of estrangement, hesitation, or defamiliarization. Ultimately, the course exposes students to a broadened conception of sustainability and a widened field for intervention through a careful examination of the supply chain of material production.

Radical Access

Brent Sturlaugson, “Radical Access,” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Annual Conference Proceedings 108 (Washington, D.C.: ACSA Press, 2020)

This paper seeks strategies by which architecture and architectural pedagogy might be radicalized toward more equitable ends. It uses a current debate in local politics as its context, and it enlists a process of continuous engagement as its method. In this case, the debate is over a text amendment to the zoning ordinance (ZOTA) of Lexington, Kentucky that would allow the construction of accessory dwelling units (ADU), and the method of engagement is based on students, faculty, and practitioners in architecture working with planners, residents, and administrators to help define the terms of the ZOTA. Together, these strategies propose a framework for design centered around the concept of radical access. While interpretations of this concept can and should vary widely, this paper presents two possibilities: how to take a radical position relative to an accessible city, and how to take a radical stance toward the accessibility of the discipline of architecture.

To begin, we formed a partnership consisting of multiple stakeholders to imagine how design might factor into the ZOTA process. The collaboration unfolded in three phases. First, we sponsored a design competition for both students and professionals. Crucially, the competition launched only weeks after the initial release of the comprehensive plan draft, which identified a need for expanded housing choices, including ADUs. An exhibition of the competition entries enabled public engagement with a range of possible solutions, and it provided a platform for the newly elected mayor to voice her support of the effort.

Second, we worked with the planning department to develop a handbook that outlines important design principles for ADUs. Guided by these principles, we designed a prototype and built a physical model for a typical residential lot. The prototype enlists passive design principles to facilitate natural heating, cooling, and lighting, as well as universal design principles to promote accessibility. To lower the impact on existing sewer infrastructure, it detains rainwater onsite for future irrigation, and to reduce its carbon footprint, many of the structural and finish materials would derive from sustainably managed forests. Conceptually, the prototype draws inspiration from the continuously changing character of the built environment. At its entry, the unit presents a roof profile that reflects much of the existing residential landscape, and toward the back, this profile is inverted to create an unconventional roof that signifies a departure from existing practices.

Third, we presented the prototype at a series of public meetings hosted by the planning department. Concerned with maintaining privacy between the main house and the ADU, the model demonstrated ways of orienting views and creating protected outdoor space. The competition entries were also on display, offering additional opportunities for public engagement with a wide range of possible designs. Reporters from local papers and television stations attended these events, and the designs featured prominently in their coverage. Ultimately, this project is an experiment in designing for radical access, understood as a root-level engagement in political processes, as well as a disciplinary reckoning with how designing for people with disabilities is understood.

Critical Spatial Practice

Brent Sturlaugson, “Critical Spatial Practice,” Society & Space (August 2019)

Faced with mounting concerns over social justice, cultural representation, environmental sustainability, political violence, and economic inequality, this panel seeks to assemble ways of intervening through ‘critical spatial practice.’ Drawing on Michel de Certeau’s ‘tactics’ and Henri Lefebvre’s ‘spaces of representation,’ feminist theorist and architectural historian Jane Rendell has proposed the concept of critical spatial practice to describe activities that create friction within existing systems of oppression. Documenting the work of radical artists and architects, Rendell’s extensive research offers an informal archive for scholars and activists seeking to intervene in the production of space. In addition to this archive of both historic and contemporary examples, Rendell also offers a list of specific qualities that characterize a critical spatial practice specifically rooted in feminist theory (collectivity, subjectivity, alterity, performativity, materiality). Joining Rendell in this effort to describe the contours of subversive acts of spatial production are Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till who outline five ways of operating as a ‘spatial agent’ (appropriation, dissemination, empowerment, networking, subversion). And more recently, Keller Easterling has proposed distinctive characteristics of ‘medium design’ as antidotes to more authoritative design practices (indeterminacy, discrepancy, temperament, latency). While important differences exist, what brings these theories together is their attention to the character or quality of spatial production, rather than its method or name. Taking these qualitative descriptions as a point of departure, this panel seeks contributions from theorists and practitioners in geography, planning, art, architecture, landscape architecture, and urban studies that critically examine spatial practices in climate change resilience, sustainable design, urban metabolism, material ecologies, interior urbanism, settler geographies, and other topics. The panel asks several questions. How is critical spatial practice defined? What does it mean to pursue critical spatial practice? Who benefits from critical spatial practice? What qualities do critical spatial practice share? How might critical spatial practice enable alternative futures?

We Have Never Been Sustainable

Brent Sturlaugson, “We Have Never Been Sustainable,” POOL 4: Nostalgia (2019)

In 2013, the curators of the Oslo Architecture Triennale—the Belgium-based collective Rotor—asserted that the perceived embrace of sustainability among design professionals “turns out to be superficial at best.” Their exhibition for the event was called “Behind the Green Door,” which sought to define sustainability in architecture not through a list of requirements but rather, through a collection of objects that represented many different definitions of sustainability. According to Rotor, “The idea exists that there is some mathematical form of sustainability. That it is just a matter of running some numbers into a computer. We disagree, and we want to show the struggle that is taking place to fabricate a concrete meaning of the notion.” What resulted was an exhibition of 600 objects, ranging from toy houses to wall sections, that together proposed a more relational understanding of sustainable design.

The spirit of “Behind the Green Door” points to a more grounded, more messy, more contingent notion of sustainability. In what might be considered an allied spirit, Bruno Latour has recently proposed a realignment of the political spectrum to more effectively address climate change. In his book, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Latour calls for a “shift from an analysis focused on a system of production to an analysis focused on a system of engendering.” Engendering, for Latour, is based on creating attachments and cultivating dependencies. In other words, a system of engendering seeks more mess, more variables, and more actors. By enrolling more, Latour argues that “we are going to be able to multiply the sources of revolt against injustice and, consequently, to increase considerably the gamut of potential allies in the struggles to come.” Through a system of engendering, the collective grows and with it the momentum to tackle such intractable problems like climate change. However momentary and partial it may have been, “Behind the Green Door” hinted at what might become of architecture if it seeks to complicate, rather than simplify, its definition of sustainability.

In order to combat climate change with any meaningful effect, architecture must reconsider its relationship to sustainability. Rather than the cold hug offered by a ‘system of production’ that concerns only humans and their use of resources, we need to invite the warm embrace offered by a ‘system of engendering’ that includes an intricate web of humans and nonhumans. With this reorientation, sustainability might finally be within our grasp. But for that to happen, the idea requires that we dwell in the messy details and often inopportune effects of architectural production.

Culture Jamming & Climate Change

Brent Sturlaugson, “Culture Jamming & Climate Change,” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Fall Conference Proceedings (Washington, D.C.: ACSA Press, 2019)

Treated with such frivolity and hubris as to be adopted by Shell, Exxon Mobil, Gazprom—and nearly every other corporation complicit in the climate crisis—sustainability has been robbed of its meaning to such an extent that recovery seems daunting. But if we are to heed the warnings of recent national and international climate change reports, recovery of a more earnest definition of sustainability is imperative. Rather than developing evermore detailed accounting methods for achieving certification, the problem of sustainability must be fundamentally reconceived. In what might be considered an allied spirit, Bruno Latour has recently proposed a realignment of the political spectrum to more effectively address climate change. In his recent book, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Latour calls for a “shift from an analysis focused on a system of production to an analysis focused on a system of engendering.” (82) Engendering, for Latour, is “based on the idea of cultivating attachments, operations that are all the more difficult because animate beings are not limited by frontiers and are constantly overlapping, embedding themselves within one another.” (83) In other words, a system of engendering seeks more mess, more variables, and more actors. By enrolling more, Latour argues that “we are going to be able to multiply the sources of revolt against injustice and, consequently, to increase considerably the gamut of potential allies in the struggles to come.” (88) Through a system of engendering, the collective grows and with it the momentum to tackle such intractable problems like climate change.

Through the practice of détournement, this paper proposes a concrete method that might help recover a more earnest definition of sustainability in architecture. Introduced by Guy Debord in the 1950s, the détournement was conceived as a way of subverting dominant narratives in popular culture. Often translated as ‘hijacking,’ the method has retained its critical edge and gained widespread popularity in what is commonly referred to as culture jamming. Using the products from several culture jamming workshops, this paper argues for a messier, more contingent notion of sustainability through the production of media that seeks to unsettle common assumptions about architectural materiality. Heeding Latour’s call for a system of engendering, participants in these workshops selected representations of everyday building materials from a range of trade publications and popular magazines and juxtaposed them with images that reveal the hidden costs of their production. At the conclusion of the workshops, participants presented their work to the group and explained the rationale of their compositions, often highlighting socially, politically, or environmentally charged narratives. These collages were collected in an archive that will be used in future culture jamming activities that target professional organizations, all of which seeks to recover a more concerted effort toward achieving sustainability in design.

What You Don’t See

Brent Sturlaugson, “What You Don't See,” Places Journal (September 2018)

In the corporate literature of Georgia-Pacific, the trademark “What You Don’t See Matters” refers to the branded building products used in many light construction projects. Understood in the context of supply chain capitalism, however, the phrase takes on new meaning. “What You Don’t See” in the production of these building products includes: 4 tons of sub-bituminous coal leaving a single mine in Wyoming every second; 22 tons of sub-bituminous coal burning at a single power plant in Georgia every minute; and, 62,000 tons of carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere every day as a result of this process. Moreover, “What You Don’t See” also includes: $10,000,000 in chief executive officer compensation at Peabody Energy; $12,000,000 in energy industry lobbying by Southern Company; and $900,000,000 in campaign spending by Koch Industries. Needless to say, it “Matters.”

This paper examines the supply chain of plywood sheathing in the material transformation of sub-bituminous coal. The argument consists of three parts. First, expanding the system boundaries of what constitutes architecture enables a more politically engaged practice. Second, enlisting visual representation in the delineation of spatial problems expands the agency of architecture in contemporary discourse. Third, envisioning alternative futures introduces the politics of possibility and leverages a uniquely architectural mode of inquiry. Together, the material and immaterial forces of supply chain capitalism reveal the complexity of production, and contribute to a more thorough understanding of the politics of design.

Design Research or Research Design?

Brent Sturlaugson, “Design Research or Research Design? The Value of History and Theory in Architecture,” Asymmetric Labors: The Economy of Architecture in Theory and Practice, eds. Aaron Cayer, Peggy Deamer, Sben Korsh, Eric Peterson, Manuel Shvartzberg (New York: The Architecture Lobby, 2016): 200-205

“Too much time was given to lightweight assignments like research at the beginning of the semester, which didn't leave enough time for design and production.” In this statement, submitted anonymously by an undergraduate architecture student at the conclusion of a third-year design studio, the labor of architectural history and theory is pitted against design. And in the end, as often happens in the studio setting, design not only rules but it rules with an iron fist, intolerant of its peers known as history and theory, or in this case, “research.”

As labor, design research, unlike architectural history and theory, is easy to quantify. Its products are material and relate to a physical environment in tangible ways, however real or speculative. Arguably, the labor invested in these projects can be counted. In this respect, design research might be considered an entrepreneurial activity in which conventional forms of valuation are familiar. Architectural history and theory, on the other hand, elides such quantification. While the labor of research activities is often clear, the intellectual labor of synthesizing information could hardly be estimated. Research design, in this sense, finds fertile territory in architectural history and theory. In my own work, as an “academic practitioner,” the distinction between research and design is fluid. Such fluidity between design research and research design, I suggest, might contribute to a more thorough understanding of value in architecture.

There and Elsewhere

Brent Sturlaugson, “There and Elsewhere: Architecture and the Political Ecological City,” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Annual Conference Proceedings 104 (Washington, D.C.: ACSA Press, 2016)

In 2012, Aaron Betsky critiqued the newly redesigned One World Trade Center (1WTC) for its lack of vision and its feeble representation of architectural aspirations in contemporary culture. His tepid response to David Childs’s design described it as “not bad, not good, but just there.” Yet 1WTC is more than “just there.” Indeed, it is both there and elsewhere. The network of actors mobilized by 1WTC offers a glimpse into a more thorough understanding of sustainability, and a more nuanced interpretation of both architecture and the city. In this reading, political ecology offers a theoretical framework for explaining the imbrication of both humans and nonhumans in disparate geographies.

This paper uses the contested designs and redesigns of 1WTC to show how architecture mediates relations of labor, capital, and nature. It argues that an architectural lens helps to explain these relations in three ways. First, architectural practice operates in a tightly controlled legal framework in which each transaction is recorded, enabling analysis to proceed through archival research. Second, architectural artifacts create a lasting impression on the built environment, the effects of which can be traced through their material network. Third, architectural representations offer techniques that go beyond verbal analysis to include visual argumentation. Despite Betsky’s critique of 1WTC as being “a beacon in a landscape of meh,” the political ecology of architecture renders the landscape—both there and elsewhere—charged for critical inquiry into what constitutes the contemporary city.

Cavate

Brent Sturlaugson, “Cavate,” Forward 213 (Fall 2013): 43-52

In many contemporary suburban environments the destructive nature of new construction is often veiled by a false consciousness of environmental sensitivity. Measures aimed at offsetting the energy consumption of single-family households, however, merely mask the inherent problems of this typology, namely the irreversible consumption of massive quantities of natural resources. While recent innovations in environmental control systems and a growing popularity of sustainable design strategies promote energy efficiency in new construction, the underlying problem remains—inordinate consumption of raw materials attributed to the residential building sector. This, in turn, contributes to an architectural pattern in which development outpaces itself.

To better understand this phenomenon, Cavate seeks to distill the elements of suburban residential development in a temporary construction based on ancient building technology. Named in relation to the habitability of earthen voids, the installation highlights the relationship between single-family detached housing and the raw material required to build it. The juxtaposition of an iconic suburban image and the void from which it came seeks to establish an immediate connection between an everyday building typology and its material origins. In doing so, the viewer is encouraged to explore this link in the built environment and consider the source of single-family housing construction.

The Minor Tonality of Arantzazu

Brent Sturlaugson, “The Minor Tonality of Arantzazu,” CLOG (2013): 98-99

At each quarter hour, successive phrases of minor tonality fill the valley surrounding the Franciscan Sanctuary of Arantzazu with an air of sobriety and reverence. Between the sloping green pastures and rocky protrusions of the Natural Park of Aizkorri-Aratz in the Basque Country, echoes of the annunciations permeate the void. At its source, the ominous tone materializes in coarsely quarried pyramidal stone that uniformly wraps the symmetrical towers and soaring bell tower of the Basilica of Arantzazu.

Built between 1950 and 1955, Francisco Javier Saenz de Oiza and Luis Laorga's design replaced earlier basilicas that had consecrated the fifteenth century pilgrimage site. Situated within a cluster of monastic buildings that emerge precipitously from the limestone cliff, the Basilica of Arantzazu holds firm to the ground on which it rests. Tucked below a Jorge Oteiza sculpture on an otherwise unadorned face, the entrance dips solemnly into the earth. Once past the cold, coarse ornamentation of the basilica’s facade, the warm wood treatment embraces the congregation while they gaze upon a naturally lit apse depicting the Virgin of Arantzazu as she appeared to a humble Basque shepherd in 1468; on their lips are the same words he spoke, imbued with a longing tone, “Thou, among the thorns?” (Arantzan zu?). Indeed, hidden among the concrete relief sculpture that decorates the apse is a miniature likeness of the Virgin of Arantzazu.

The building emerged out of an artistically repressive regime under General Francisco Franco. Only by virtue of its Catholic allegiance was construction permitted, despite the dictatorship's attempted annihilation of Basque identity. Symbolically inscribed in the austere detailing and chilling materiality is the memory of the 1937 bombing of Guernica. What emerged in an era of persecution now represents an icon of Basque arts and heritage.

At the top of each hour, the minor tonality of Arantzazu resolves with a major chord. For fifty-nine minutes of every hour, tension courses through the air, but in the minute following the new hour, the setting becomes wholesome and complete. During this fleeting moment, the once brusque and foreboding materiality of the basilica appears protective and haven-like. Sounds that have washed the setting in desperation conclude with notes of promise. In the plaza shaped by the north side of the sanctuary and a vertical rock face, local shepherds sell homemade cheese and bread. Inside, pilgrims participate in services orated in Basque, a practice outlawed under Franco. Surrounding the sanctuary, this harmony is reflected in pastoral scenes of collective, rural life that populate the undulating landscape.

In a built environment that often values consonance among its parts, examples of dissonance stand out. At the Basilica of Arantzazu, the harsh materiality and geometry of its exterior is broadcast throughout the valley every fifteen minutes, reminding listeners of its somber past. The presence of the basilica and its inescapable dissonance highlights the harmonious context in which it resides. Only at the conclusion of each hour, as the progressive minor phrases resolve in major tonality, does the environment regain stasis.